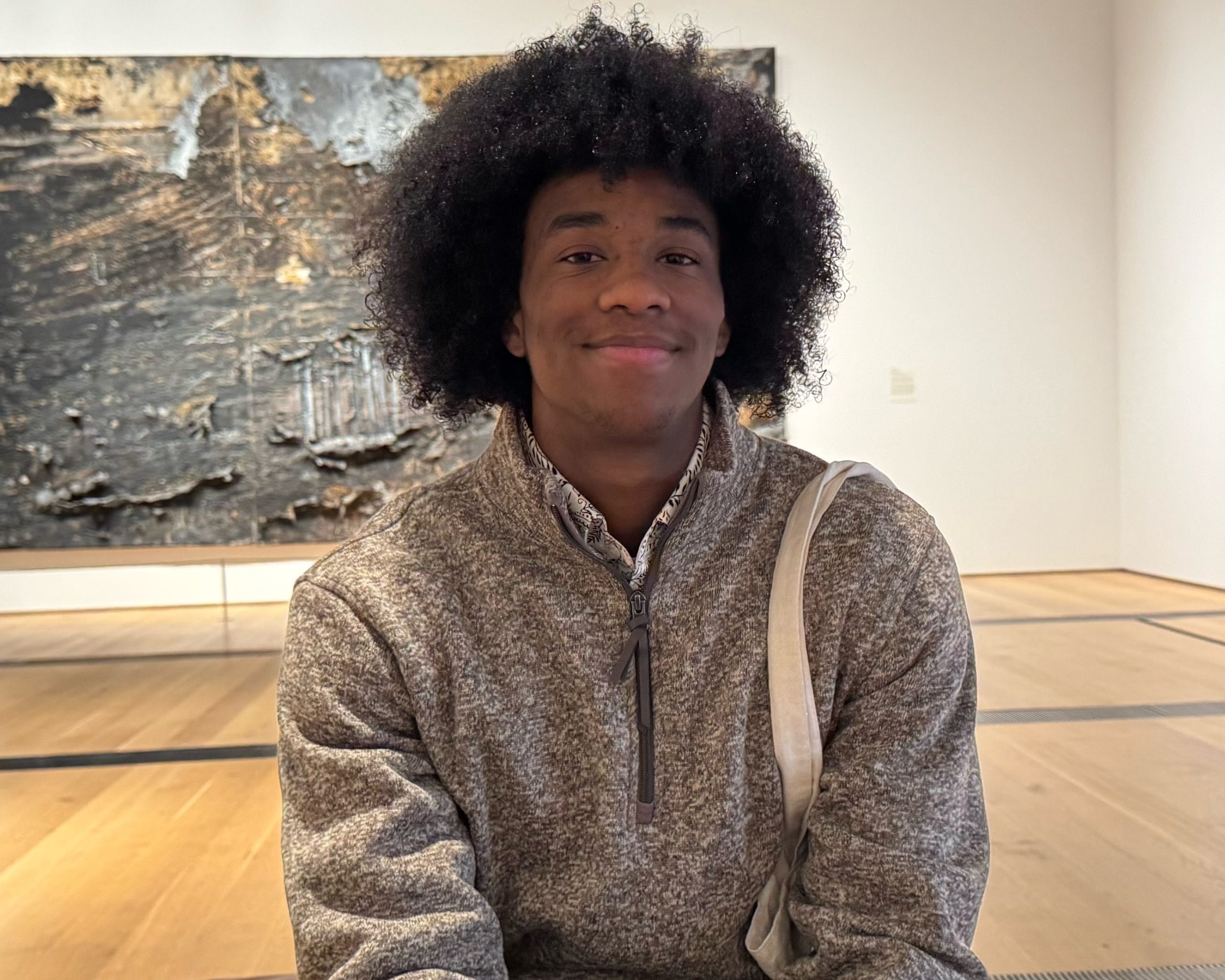

Befriending someone on death row – LifeLines member Noah shares his experience

The Voice, 21 July 2025.

“Even with the knowledge of the crime my penfriend was convicted of, I see no ethical dilemma in upholding his humanity”.

Noah Mayo has been writing to his penfriend, Lee, on death row in the United States for two years after joining the UK registered charity, LifeLines. A law student from Chicago, Noah heard about the charity while studying in Oxford on an international exchange.

Established in 1988, LifeLines supports and befriends people on death row in the United States through letter writing and email. Founder Jan Arriens was inspired by watching the 1987 BBC documentary Fourteen Days in May. The programme followed a young black man, Edward Earl Johnson, in the days before his execution and the attempts of Clive Stafford Smith to save his life (Stafford Smith is now a renowned human rights lawyer and LifeLines’s patron).

Moved not just by Johnson’s execution but also by the humanity he and the other men interviewed showed, Arriens wrote to them and, when he found he couldn’t maintain a correspondence with them all, his friends stepped in to help. And so, LifeLines was born and today has nearly 1,000 members, mostly UK-based but with an international contingent, including Noah.

Now back in the US studying law at Washington University in St Louis, Noah explains he joined LifeLines because he saw writing to someone on death row as, “a great opportunity to have an important and immediate impact in the lives of some of the most vulnerable people in our society”.

While LifeLines does not take a position on the death penalty, members have their own views. For Noah, his opposition to the death penalty is a key driver for writing to Lee, as their relationship ensures he doesn’t forget why change is needed. He also reflects that policy change “cannot be done in a single day. Yet today we can exchange a childhood memory with a penfriend and realize it does not differ all that much, or we can learn his favorite poems, or remind him of his dignity”.

Noah, like many LifeLines members, makes clear it’s not just Lee who benefits from their correspondence. At 61-years-old to Noah’s 23-years, Lee is old enough to be Noah’s grandfather. Although that might not sound like an auspicious start to a friendship, Noah reflects that “it has changed the way I appreciate having a grandfather-like figure. … During the course of getting to know Lee, it has been wonderful to hear his advice and to listen to what he would have done differently at various stages of his life”, Noah explains. “He also reminds me to focus on what will remain important over the long term. There are many things which may occupy much thought today but will be insignificant in one, five, or ten years. … This has been quite an important lesson”.

He also says they “push each other to do things which are outside our typical patterns”. This is obviously more of a challenge for Lee on death row but, unlike in a lot of states, he does at least get to leave his cell unshackled for most of the day. Conditions elsewhere are much more restrictive, like Texas where men are kept in isolation and only allowed out of their cells individually for an hour or two per day.

In contrast, Lee can exercise with other men from ‘the row’ and has access to some educational programmes, like art classes where he can paint; something that inspired Noah to get creative himself, art being one of their shared interests.

However, none of this can erase the fact that the state where Lee is imprisoned recently began carrying out executions again. “There was a heavy tension and much stress for many upon learning the news”, Noah says Lee told him. “Probably the most difficult time Lee shared with me was when another man on death row was moved to what they call the ‘death house’ after the [state] government set an execution date for him. … Lee conveyed more confusion than frustration at the fact the government would continue trying to execute this man as he was on the verge of death in the hospital.”

While Noah was encouraged to learn that Lee believes “his appeals will likely outlast his life”, anyone joining LifeLines needs to be prepared for the possibility their penfriend could be executed, depending on their circumstances and the state they are in. For support with this and other difficulties members might encounter, LifeLines provides a caring community, access to volunteer counsellors and a dedicated coordinator for each state.

Opportunities to engage with other members include LifeLines’s twice yearly conferences where members hear from inspiring speakers. Like Anthony Ray Hinton, who spent nearly 30 years on Alabama’s death row before being exonerated, and Equal Justice Initiative director and public interest lawyer Bryan Stevenson, who fought for Hinton’s freedom.

Hinton is one of nearly 200 people released from death row for crimes they didn’t commit and, like many of them, racial bias was a significant factor in his case. This bias is a thread that runs throughout the death penalty and can be seen in the fact that 40% of people on death row across the US are black, despite black people making up only 13.7% of the US population.

Given everything that people on death row face, it is not hard to imagine why letters or emails from the outside world are so treasured, as Noah knows they are for Lee.

“It has been a pleasure getting to know Lee over the past two years and I will keep writing him because he has shared with me how much our relationship means to his life, and I know what it means to mine.”