From death row inmate to acclaimed author

Story by Erwin James, The Guardian, 31 May 2011.

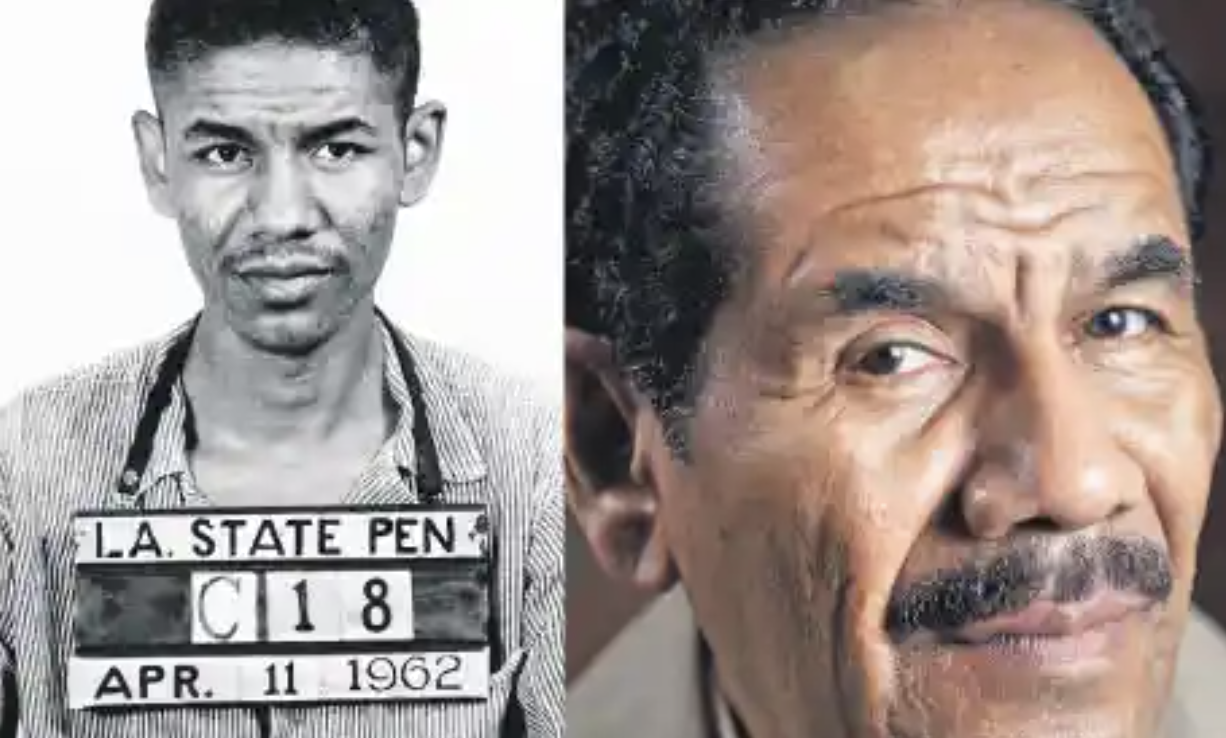

Wilbert Rideau spent 44 years behind bars. Now he’s campaigning for society to help prisoners start a new life.

I first encountered Wilbert Rideau in a high-security prison in 1999, when I was 15 years into my own life sentence. Sitting in a classroom alongside a dozen other lifers, I watched a video of the academy award-nominated documentary The Farm: Angola, USA, which Rideau had co-directed. The film followed the lives of a number of prisoners in the Louisiana State Penitentiary, a former slave plantation worked by men and women stolen from Angola, Africa, hence the prison’s dark sobriquet. The prisoners shown in the film had already served decades longer inside than any of us watching. To a man, we were gripped. At the time of the film’s making Rideau had been in prison for 37 years, yet his intellect, his wit and his enthusiasm for life remained intact.

Knowing how much of a struggle it was to stay mentally alive on the long-term wings and landings of UK prisons, never mind physically alive, I couldn’t help admiring Rideau for what he was achieving in Angola, once dubbed “the bloodiest prison in America”. His attitude was all the more remarkable since his chances of ever being released were so slim. Ninety per cent of Angola’s prisoners are expected to die there.

But Rideau’s particular appeal for me was the fact that it was in prison that he discovered an ability and a passion for writing. In this respect there were huge echoes of my own prison experience, although his beginnings were far less promising than mine. Sentenced to death aged just 19, there was little hope he would ever experience real life again. He was bright, but had gained little from his state education. His real education, he says, came from the books he read while being held for 12 years in an isolation cell on death row. Some were lent to him by guards who were students at Louisiana State University. The Fabric of Society, by Ralph Ross and Ernest van den Haag, gave him, “a basic understanding of society and human behaviour, including my own”. Machiavelli’s The Prince provided insights into the nature of power and politics, “the forces which ruled my life”. And from Morris West’s Shoes of the Fisherman he learned that “pain is the price of living”.

After his death sentence was commuted to life when the US supreme court briefly suspended the death penalty in 1972, Rideau joined the general prisoner population of Angola. In 1974 he began writing a syndicated newspaper column entitled the Jungle, the first of its kind by a serving prisoner. In 1975 he became editor of the Angolite, Angola prison’s magazine, a role that he held for more than 20 years. Under his stewardship the Angolite won a raft of major awards, and was the only uncensored prison magazine in the US. Unlike British prison magazines, which tend to be uncontroversial and filled with prisoner contributions, the Angolite operated to professional journalistic standards and tackled serious issues, such as sexual slavery in prison. Rideau branched into radio journalism and film-making and in 1993 Life magazine called him “the most rehabilitated prisoner in America”.

The rehabilitation of prisoners, especially those who have committed the most serious offences, divides law-abiding people everywhere, and it is a good subject to discuss with Rideau when I get the chance to speak to him at last. For a man who has spent 44 years in prison, he looks remarkably well preserved. Now 68, he was released five years ago after a jury at his fourth retrial threw out his 1962 murder conviction and found him guilty of manslaughter instead. He is in the UK to talk about his autobiography, In the Place of Justice: A Story of Punishment and Deliverance.

“Rehabilitation means living a better way,” he says. “For those who have committed crimes, it means changing the way you live so you are no longer committing crimes. It’s about doing good instead of bad.” For all the 20 years I spent in prison I never heard any fellow prisoners talking about rehabilitation as part of their prison journey. I met thousands who were trying to use their time preparing to live better lives once they were released. But that “R” word seemed to belong to other people – to journalists or politicians. Despite the presence of teachers, counsellors and various others whose job it was to assist in helping the prisoners live crime-free lives, the overall prison experience felt geared to hinder efforts to change for the better. “Let me tell you,” says Rideau, “in the US there is no more education, training, ‘rehabilitation’. Hell, they have done away with all that stuff. It costs too much money. There are religious groups who will come into a prison for free and give bible teaching. That’s pretty widespread. Of course, people in prison have to want to change, but prison life is primarily about survival.”

I guess for many people outside, it doesn’t really matter too much how difficult life in prison might be. As former home secretary Michael Howard once announced to much applause: “If you can’t do the time, don’t do the crime.” There will always be people who believe that punishment, especially for the most serious crimes, should be severe. And yet, here we both are, by the grace of our respective societies, allowed to live again and take part in our communities as regular citizens. “Well, I like to think that I represent the potential that exists for all those guys, because I know they want to be better than who they are – not necessarily turning out to be writers – but plumbers, electricians, artists, a whole bunch of other things. When it came the time for me to want to do something good my life had been reduced to paper and pencil and a cell. Had I had access to other things, I might have done something different. But that’s all I had. So I was forced to become a writer. It was a fluke.”

Why did he think that society was so reluctant to accept that people such as him and me, people who have seriously harmed others, truly have the capacity to change and to contribute? “The public is misinformed about the realities of crime and criminals, of what they need to do to deal with it. It is also a case of failed political leadership. The leaders fail the people, because rather than seek to find real solutions, they seek to gather political mileage instead. And the media fails because it thrives on creating conflict, focusing on the most sensational aspects of crime. They demonise us, and you can’t blame the public for not trusting that we might be able to come out and live decently among them.”

Rideau was a couple of days past his 19th birthday, when for reasons that make no sense at all, he bought a gun and a knife from a pawnshop in Lake Charles, Louisiana, and decided to rob the bank just a few blocks from where he worked. Within a couple of hours of the holdup, two of his hostages were wounded and the third lay dead. All were white. Rideau was arrested shortly afterwards and confessed to the crime in the sheriff’s office, in front of television news cameras. This was at a time of acute racial segregation in Louisiana, and Rideau was in serious danger of being lynched. He gives a terrifying account of what happened next in his book. But the one thing that disturbs me is that he also writes a graphic account of his actions as he perpetrated his crime.

With the reduction of his murder conviction to manslaughter, the loss felt by the family of his victim will not have lessened. Despite his obvious remorse and regret, was it not insensitive in the extreme to write about what he had done in such detail? “I never wanted to write about that, not ever. And I never talk about it. But my editor said to me, ‘We can’t publish a book about a guy who spent 44 years in prison and not make any mention about what he did.’ I had to think long and hard about it; certainly I would not have chosen to do it. But I had to write that book. I’ve learned so much from what I did and from what happened to me. I want other people to be able to learn from it too.”

I tell him I experienced punishment from a very young age and I can’t say hand on heart that it ever did me or anyone else any good. Rideau has experienced several lifetimes’ worth of punishment. Did he think it had any intrinsic merit? “Listen,” he says, and looks hard at the table between us. When he lifts his head he looks directly into my eyes. “To punish somebody you have to injure them. Right? Well let me tell you, I never knew a single person who was ever improved by injury.”

I know from my own experience that most people in prison have the desire to change for the better. But persuading the public that this should be the main focus of prison is a hard task. “Well, if your objective is to punish the guy, hell, you can shoot him and be done with it. If it’s to keep him locked up, you can put him in a kennel and just forget about him. But if you are not going to kill him or keep him in there for life, he’s coming back out. This is not a political issue one way or the other – this is a common-sense issue.

“If you send a guy to prison because he is irresponsible, violent, a criminal, you should want him to come out better than he was when he went in. That’s common sense. That is to protect your own ass. If we don’t help him to adjust to society, to want to be a part of society, he’s going to rob or steal again. He’s going to follow the most basic law in life, the law of the jungle.”

What would he say to anyone who argues that rehabilitation is an insult to victims? “No, I don’t believe that. People who have been harmed by others have a right feel anger, to feel bitter. They’re not interested in any rehabilitation and they are absolutely entitled to feel the way they feel. But for the preservation of society, for the good of society, by helping people to live good lives after prison we are doing more to reduce the number of future victims.”

I hoped so much that would be his answer.

Article with kind permission of the Guardian – original source www.theguardian.com/society/2011/may/31/wilbert-rideau-rehabilitate-prisoners

Tags: Announcement